By Lorna Dielentheis

The winter before last, I spent the whole season teaching myself trees.

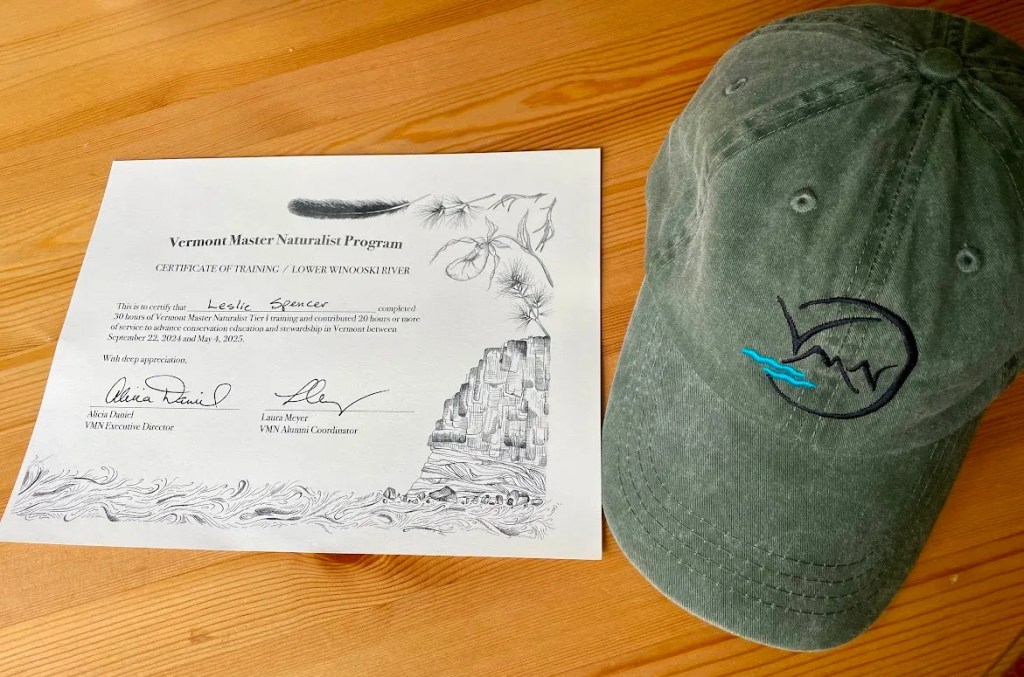

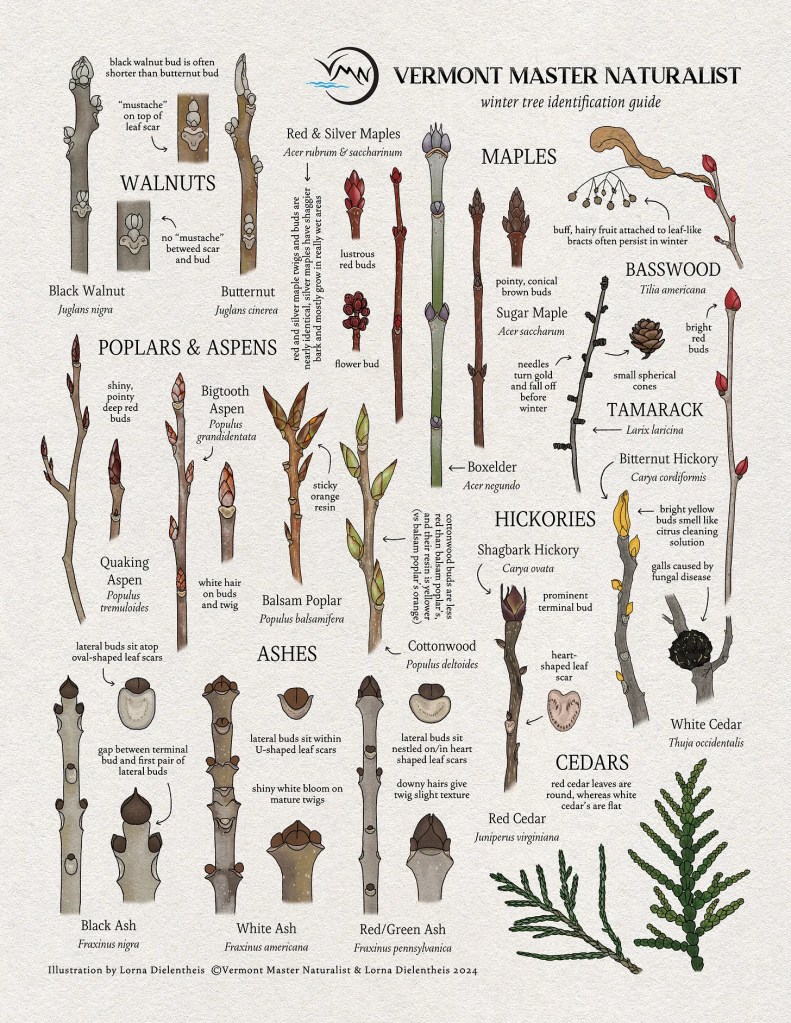

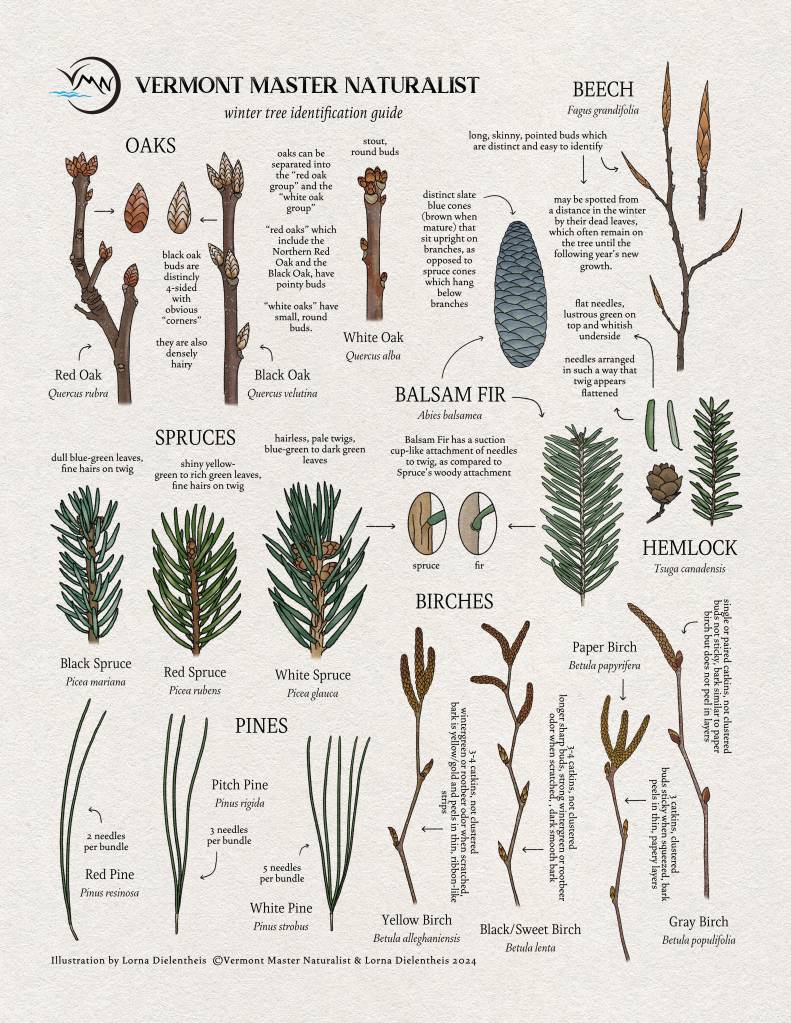

I’d been introduced to tree ID before, had tried to memorize each species’ unique characteristics, and spent hours working my way through keys in various field guides. But the knowledge didn’t stick. It came and went, as fleeting as the leaves I pored over. Then in the fall of 2023 I was met with an incredible opportunity: to create an illustrated winter twig guide for one of my favorite clients, Vermont Master Naturalist.

On a sunny fall afternoon, Alicia and I sat on her porch and talked twigs. Alicia is the founder and director of Vermont Master Naturalist, a program that teaches natural history from a holistic perspective and builds community around conservation and local ecology. I completed the VMN program in 2021, am currently in the Tier II program, and can genuinely say it has changed my life. The first time around, VMN solidified my passion for nature study and now, it continues to instill the confidence I need to pursue this path in a more serious way.

I was both elated and overwhelmed as we looked through a stack of books together and started brainstorming what we wanted our winter twig guide to look like. I nervously admitted to Alicia that my tree ID skills were mediocre at best, and she reassured me that not only would I learn, but that my lack of knowledge was an advantage: I could use my own learning experience to determine what ID characteristics were most useful to a beginner.

twigs from left to right: striped maple, white ash, sugar maple

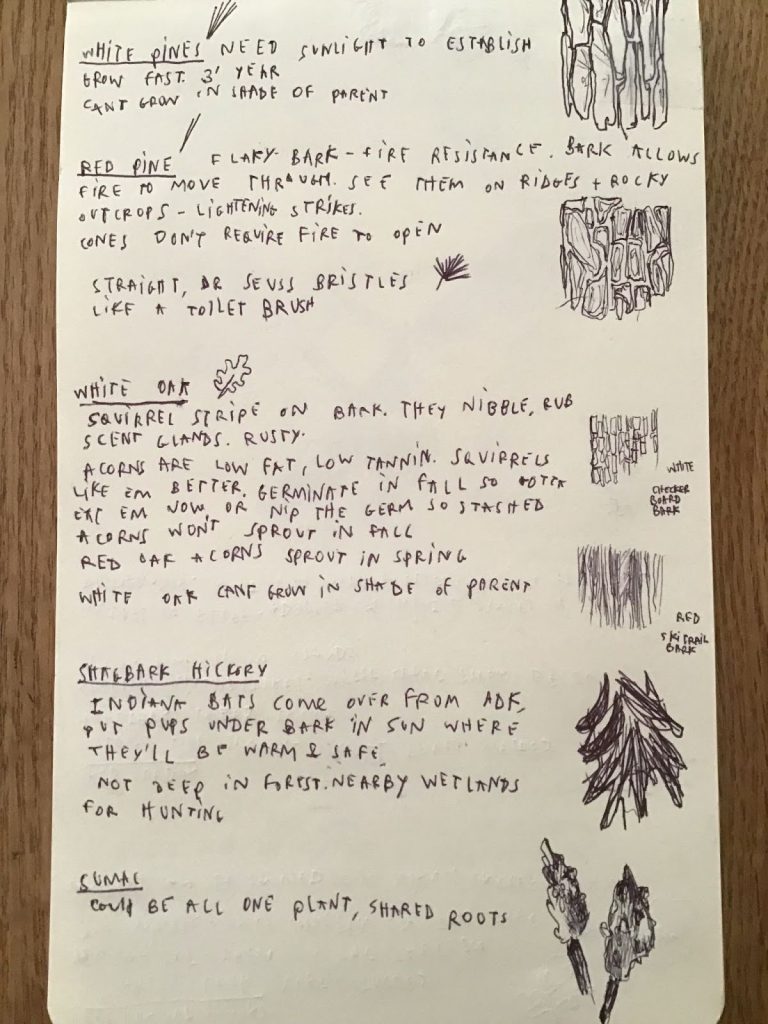

Throughout that fall and into early winter, I set my mind to learning trees once more. But instead of trying to memorize every single characteristic of each tree like I’d done before (bark texture, leaf shape, branch arrangement, pith, soil conditions, etc), I focused solely on the winter twig. It was this method of close study, careful observation, and of paring down the scope of my learning that finally made the trees stick with me.

Don’t get me wrong– at first, it was really hard. I didn’t trust myself; I was hyper aware of how much I did not know. What if a bud kind of looked like the pictures in a field guide, but not quite? How do I tell what’s natural variation, versus a different tree entirely? How hairy is “hairy”? Of course this is why dichotomous keys exist, but having a basic understanding of what a key is even asking requires a significant amount of knowledge. I found that when I was out in the field, and especially as the days were getting shorter and colder, I didn’t have the resources or time to look up every scientific term I didn’t know.

Instead, I began carrying a set of clippers and ziploc bags in my trail pack. I’d take pictures of a tree and note where I found it, taking a twig home with me for further investigation. Later, when I’d dump out my ziplocs of unlabeled twigs, sometimes finding one broken to pieces or otherwise compromised by the chaos of my trail pack, I’d worry my methods were haphazard. But over time I worked out the kinks and eventually the learning structure became routine.

After the first month or so, I began to have an awareness of what trees were around me, and my searches became more focused on seeking out particular species. Perhaps most importantly, my confidence grew– not only in my ability to identify trees, but in myself.

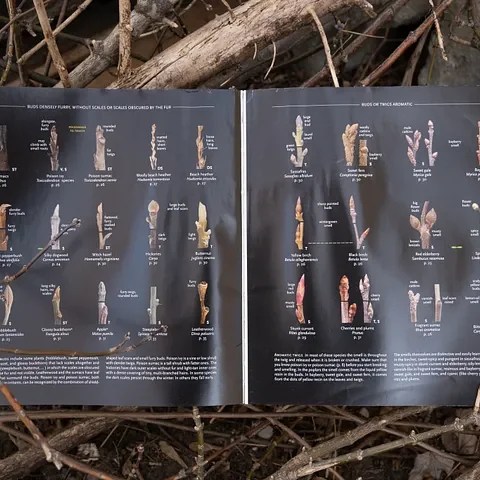

The finished winter twig guide I created 1/2

The finished winter twig guide I created 2/2

Notes on Self-teaching

It’s vulnerable to teach yourself a skill. You don’t know what you don’t know, and you’re responsible not only for the actual learning but also for creating the curriculum to structure it. It’s not like taking a class or going to school, where you’re provided with all of the correct information, and the guidance, expertise, and deadlines you need to absorb it. When you teach yourself a skill, you have to self-motivate and hold yourself accountable; you have to know when to trust yourself, and when to reach out for help.

As lonely and difficult as it can be, teaching yourself something is also incredibly empowering. It’s an exercise in self-acceptance and self-reliance, a test of dedication and grit. I have never been more proud than when I’ve taught myself new skills. And despite all of the challenges of self-teaching, you do have one key advantage: you can tailor your teaching methods to your individual style of learning. For me, this means a lot of visual and field study and less book learning. It also means incorporating art into my learning– photographing and sketching twigs helped them stick in my brain much better than flash cards or highlighting a textbook would have.

With that said, take the guidance I provide with a grain of salt; this is what worked for me, it may not be what works for you. But now, without further ado: my guide to teaching yourself trees in the winter. Or to teaching yourself anything in nature, really– though I am writing this in reference to winter twigs, the advice applies broadly.

twigs from left to right: swamp white oak, black walnut

Learning to Look

When you start learning trees, everything looks similar. There’s a period of time when you just have to soak up as much visual information as possible in order to calibrate yourself. Before you task yourself with identification, I recommend heading outside to look at a bunch of trees, any trees, to accustom yourself with the breadth of variation, the similarities and differences between species and individuals. It doesn’t matter if you know what kind of tree it is at this point, in fact I encourage you to put the urge to identify aside for the moment. The goal here is to familiarize yourself with the act of observation.

Run your hands over the bark of the tree and think about the texture– what words would you use to describe it? Is it corky and pliable, flaky, rough, or smooth? Look at the way the branches sit. Do they grow perpendicular to the trunk, or curve upwards? Do they zig-zag or tangle? Find something about the tree you think could easily go unnoticed, then let yourself be drawn to a part of the tree you find beautiful. Maybe it’s a bright yellow bud, or the tiny white dots speckling a young branch. Step back and look out at the landscape, and down at your feet. What is the soil like, how does the air smell? There are a million things to notice about this tree, and none of them require prior knowledge. You will learn all of the terminology in time; what’s most important at the beginning is learning how to look.

leaf scars from left to right, top to bottom: shagbark hickory, basswood, white ash, black walnut, red oak, another shagbark hickory

This practice applies to most forms of nature study, and beyond that is an exercise akin to meditation. As a person who struggles with anxiety, I’ve been suggested a very similar methodology countless times: “have you tried doing a grounding exercise?” The core actions are the same– engage your senses and notice what’s around you in order to guide your anxious mind back to your physical body. Although I roll my eyes a bit at the simplicity of it, I have to admit it often works, at least temporarily. And I don’t think it’s a coincidence that each time I come home from a nature excursion, I feel lighter, more secure, and more attuned to myself and to what’s important in life. Even if you never learn the names of trees, being in the moment with what’s around you is a habit worth cultivating and can have a profound effect on your state of being.

twig of a red oak

Curate Your Resources

When teaching yourself anything, it is critical to have good resources, though what constitutes a “good resource” will look different to each person. For me, it’s got to be detailed, but also easy to find the information I’m looking for. I like field guides that are largely visual and don’t require me to hunt through paragraphs of text to glean important information.

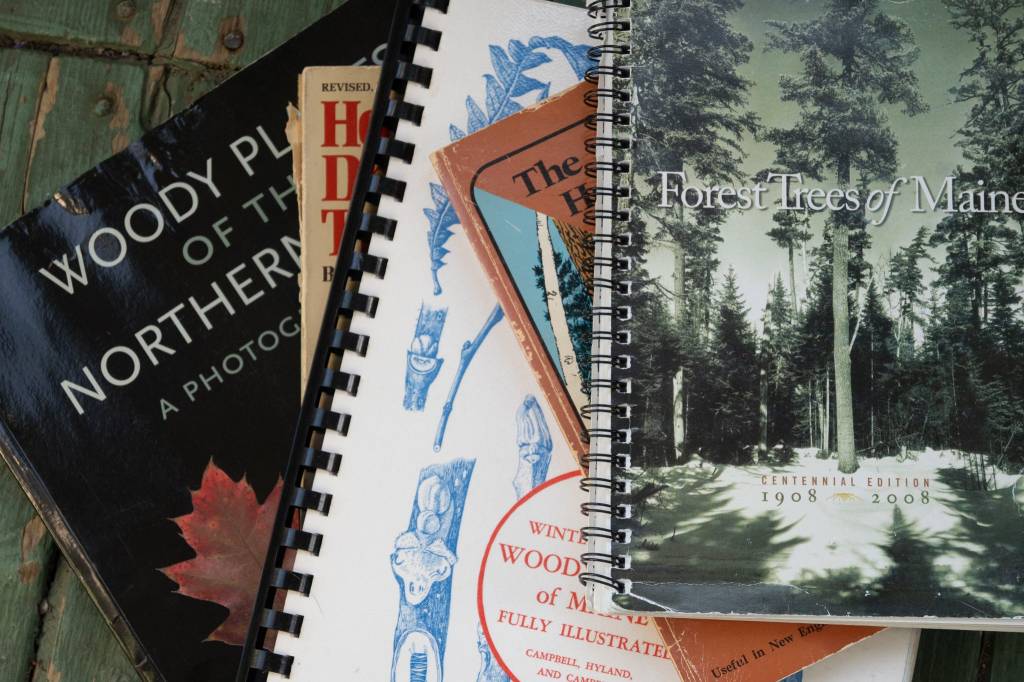

The best way to figure out what resources are going to be most useful to you is to start with far more than you think you’ll need. Check a bunch out from the library, peek at what your friends are using. Familiarize yourself with each of them, and see which ones you reach for. It’s unlikely you’re going to be able to rely on a single field guide; instead, plan to refer to a few trusted books and websites in order to paint a full picture of your subject.

These are the guides and websites I use most frequently in tree ID, and why I like each of them (and keep in mind, I am in the Northeastern United States, which many of these guides are specific to):

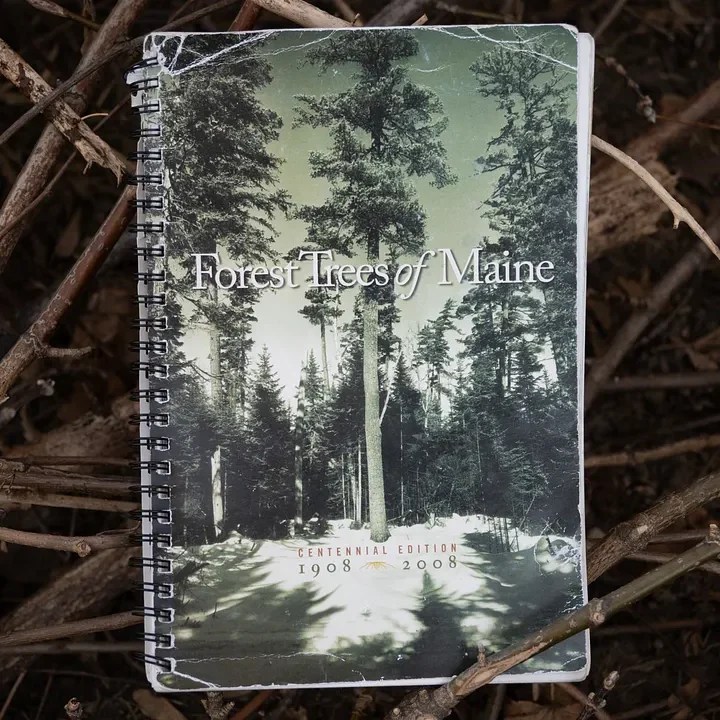

- The Forest Trees of Maine, by the Maine Forest Service.

This is the first tree guide I used. I was introduced to it through VMN, and it is still the guide I reference the most. It is simple, easy to carry out into the field, and has all the right information. It’s relevant for most of the Northeastern United States, not just Maine. If you can only get one tree guide, this is the one. It’s also available to view/download free as PDFs from the Maine Forestry Dept. website.

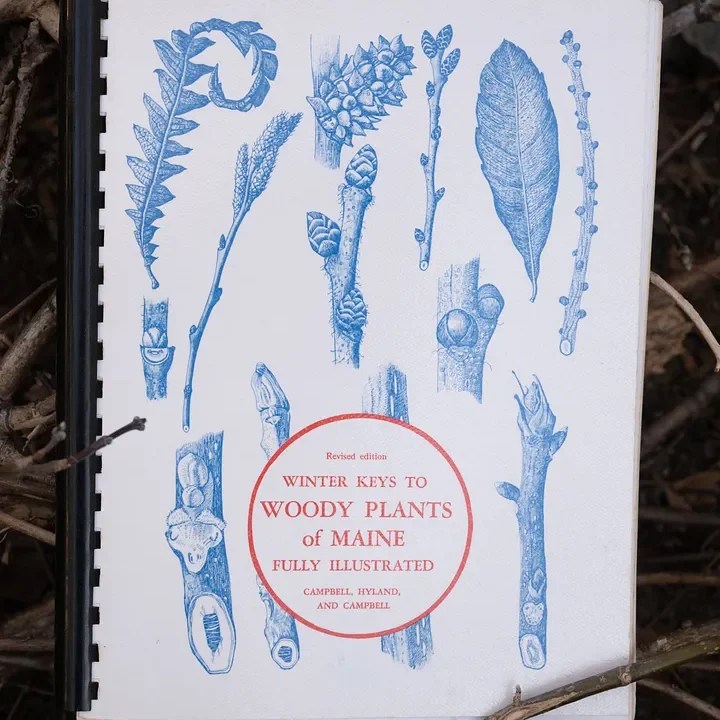

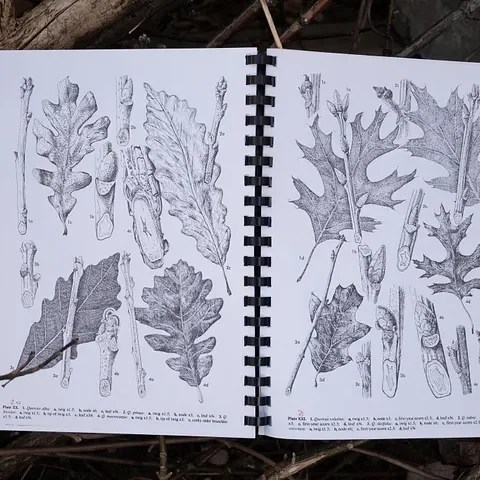

- Winter Keys to the Woody Plants of Maine, Illustrated by Mary L.F. Campbell

This book is filled with highly detailed illustrations of winter twigs. It’s out of print, and hard to find for a reasonable price. I was lucky to find a copy on eBay for $50, after borrowing one from Alicia while working on my twig guide. I wouldn’t say this book is necessary to have, but if you’re getting really deep into the subtle differences between closely related species’ winter twigs, this is a great addition to your collection. And the illustrations are so, so gorgeous.

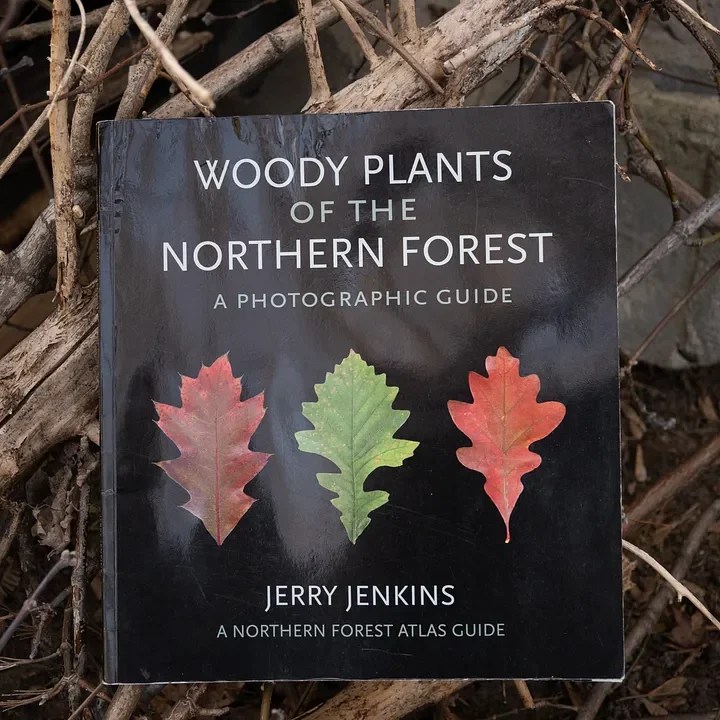

- Woody Plants of the Northern Forest by Jerry Jenkins

This is a great one for beginners because it’s photo-heavy and provides direct comparisons of visually similar twigs and leaves. You can also view and download this resource for free on the Northern Forest Atlas website, along with several other invaluable photographic guides. The only downside to this book is that it’s not great for taking out in the field– it’s large (though thin) and awkward to stick in a backpack.

This author/organization is also coming out with a far more robust version of this guide on Nov. 15, which includes a lot more species (not just trees, but many other woody plants too), called Field Guide to the Woody Plants of the Northern Forest. I pre-ordered it from my local bookstore and they goofed and gave it to me early! Lucky me. I haven’t taken it out in the field yet, but I can already tell it’s gonna be a go-to, and especially useful for my natural community visits. However, for a beginner, I’d recommend starting with the pared-down version.

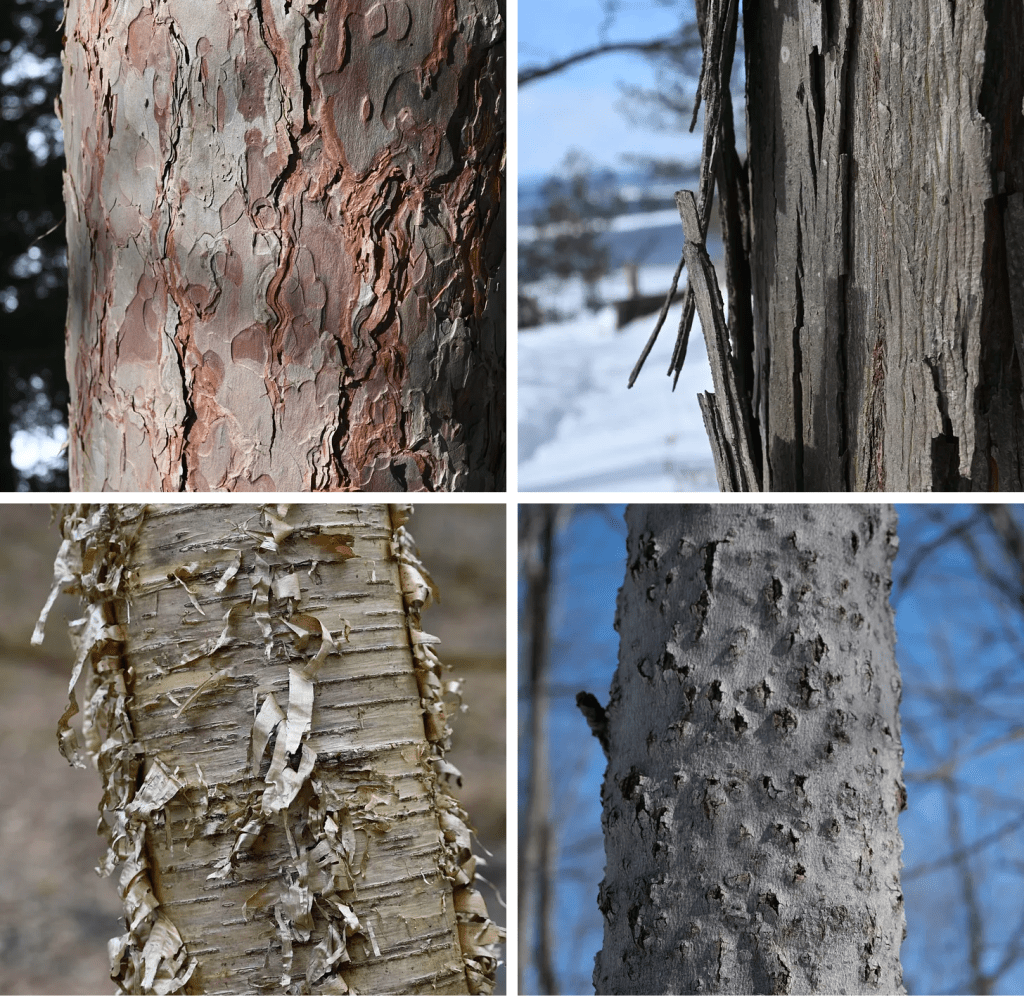

- Bark by Michael Wojtech

Bark is what it sounds like– a field guide to trees based solely on bark. This is a great accompaniment to your twig learning. I learned twigs alone, and am aiming to get better at identifying bark this winter, but learning them together would provide you with all the tools you need to ID a tree in any season. I’ve taken this guide out in the field a few times now and wish I’d bought it sooner.

a few examples of trees with really distinct bark, from left to right, top to bottom: red pine, shagbark hickory, yellow birch, beech (diseased)

- Go Botany, an online resource by Native Plant Trust

There are numerous online resources, but this is the best and most reliable source of information I’ve found for plants, including trees.

- iNaturalist, a global community science database

I know I plug iNat every chance I get, but I can’t stress enough what a powerful learning tool it is when used correctly. By this I mean– don’t use it to ID the trees. You won’t learn by doing that. Use it for finding particular species of trees, tracking patterns (what grows where? etc.), and keeping a digital log of the trees you’re learning. It’s also great for helping to gauge how much variation there is among species, since there are tons of photos to look at.

Start Small

Once you’ve gathered your resources, you’re ready to begin your study. Again, you don’t need to know much before you go out to look at trees. Familiarize yourself with some basic terminology, then get outside with a field guide or two! You will learn more through curiosity and observation than you will studying from a book. Let yourself explore and form questions, then bring those queries back to your stack of resources.

a diseased beech on a beautiful winter day

I like to start with a single tree (or bird, or flower, or whatever you’re studying, again this method applies broadly), the first one that piques your interest. Spend some time with it, use whatever guides you were able to carry into the field, and see what you can figure out. Don’t beat yourself up if you get stumped (pun intended). You probably will if this is the first tree you’re trying to ID. Remember you are learning something new, and it will take some time to feel competency. Start small and return to the sensory exercise if you get stuck. Take pictures/notes and look it up later if that works better for you.

The Tiny Beauty of Twigs

Trees are fun to learn in any season, but there’s something particularly magical about learning trees from their winter twigs. They look like tiny fairy scepters, wizard’s wands, or elaborate walking sticks in miniature. Each twig is unique, each a work of art. Finding beauty in their minute yet ubiquitous presence can transform your experience of the bare winter season.

one of the most fairy scepter-like twigs, that of a shagbark hickory

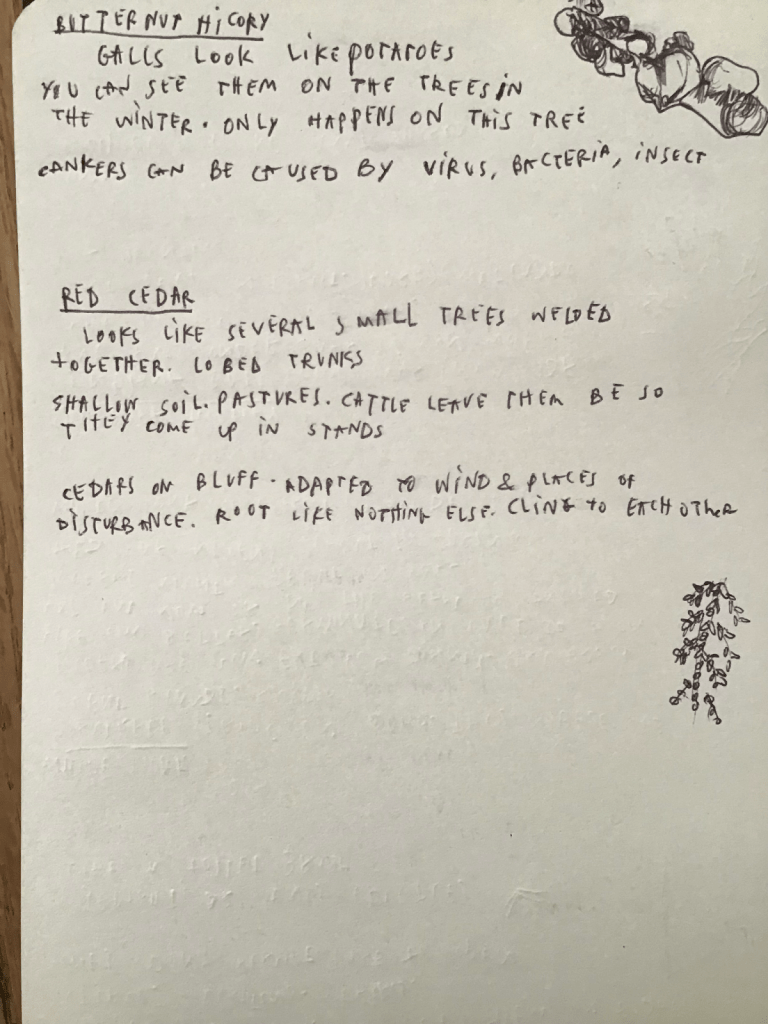

Twigs hold a lot of clues that can aid in identification. Buds alone contain so much detail– their arrangement, shape, color, number of scales, and texture are just a few of the traits that point to an ID. And then the twig itself: its thickness, pores, hairiness, pruinosity… the list goes on. And although the winter twigs are just one small part of a tree, I guarantee as you learn them you’ll pick up other knowledge, too. You’ll notice shagbark hickory’s distinct bark, and the way its branches curve enthusiastically, like arms thrown up in celebration. You might see a strange, target-like pattern on a tree’s trunk and find that it can be a useful field ID for red maples. Maybe you’ll start to wonder why the majority of the ash twigs you study are on small saplings, or shoots regenerating from stumps (more on that here).

a shagbark hickory’s distinct bark, target canker on a red maple trunk, an ash sprouting from its stump

The more you look, the more you learn. Developing a sense of wonder and curiosity, which you no doubt have already or you wouldn’t be reading this, will lead you to knowledge. That, and putting yourself in nature again and again— practice, time, and experience are essential.

As you cultivate the habit of looking closely at twigs, you’ll begin to grasp the complexity and nuance of each individual species. You’ll start to notice and unravel the million other small mysteries that await each time you go outside. And, undoubtedly, you’ll come to recognize the beauty in all the minutiae of this world.

quaking aspen twig

This post was originally published here.