By Lorna Dielentheis, VMN Mad River Tier II participant

Note: I wrote this reflection and then realized I never properly introduced the natural communities I visited! The two communities I focused on while at Peacham Bog were the Black Spruce Woodland Bog and the Dwarf Shrub Bog. At Peacham Bog (and this is the case for many bogs), there is a gradation between related communities which also includes Black Spruce Swamp and Poor Fen community types.

At last we emerge from the damp, buggy woods. The open blue sky greets us, sunshine pouring over the expanse of mossy peat stretching out into the distance. The whole basin seems to glow. Towering black spruce trees loom like sentinels as we step onto the narrow, overgrown boardwalk, while little tufts of cotton grass cheerfully dot the lush greenery beneath. The strange waxy forms of purple pitcher plant flowers lend an air of surreality to the landscape, as if we’ve just stepped into another world entirely. In some ways, we have– the ecology here is completely different from that of the land surrounding it. Though perhaps stepping into another time would be a more appropriate description.

The entrance to Peacham Bog

Tussock cottongrass, purple pitcher plant flower

13,000 years ago, a melting glacier left a shallow depression in the earth where we now stand. Acidic rainwater collected in this basin. Stagnant and cut off from other water sources, this nutrient and mineral-poor water lacked the aquatic microbes that would normally aid in decomposition. So as sedges, sphagnum, and other plants invaded the water, their intact remains accumulated and compressed over time to form a floating mat of peat.

The sphagnum moss, which thrives in these tough conditions, now blankets the peatland as far as the eye can see. This dense layer of saturated moss insulates the acidic water beneath and reinforces the cold, low-oxygen, nutrient-poor conditions, encouraging more and more peat buildup. Eventually this self-fulfilling cycle can (and does, at Peacham Bog) form a dome that elevates the acidic center of the bog above the surrounding water table.

me photographing a pitcher plant flower, sphagnum moss

The overgrown boardwalk

As we venture further into the bog, I’m struck by the vastness of this place. I’ve been to a few other bogs, but never one this big. And never to one where I’ve felt such a palpable sense of fullness– as if the bog is bursting from its container (it literally is).

The worn wooden planks depress as I walk on them, small amounts of water seeping through the slats. I wonder whether they’re secured at all or just set gently upon the peat. It feels as though, given a few days without human presence, the bog might swallow them up entirely. The low shrubby plants brush wetly against my legs, and when I kneel to photograph a pitcher plant I imagine sinking into the surrounding sphagnum. How quickly would it grow up around my body, my face?

Pitcher plants (and other bog plants) emerging from the sphagnum

I continue on, setting aside the urge to examine each plant and instead tuning into the otherworldliness of the ecosystem as a whole. There will be plenty of time to survey the plant species and take photos later. So much of my enjoyment of nature comes from its indescribable presence, the sense of place that forms when I spend time simply absorbing the interconnected beauty of it all.

It’s easy to zoom in on singular details –the strange plants, the rare butterflies, the birdsong– and boy do I love that type of niche observational study. But each of these pieces interact with each other and the whole in a way that, when understood, touches on the profound. Imagining a place as an entity unto itself composed of many smaller entities, each essential, imparts a sense of both the fragility and the expansiveness of the natural world. Compromise one element of this carefully balanced system and the repercussions can be catastrophic.

Peacham bog viewing platform

The sign at the lookout platform reads: “Peacham Bog… Nature’s Pickle Barrel.” And indeed, the acidic peat is known to preserve the remains of any creature who dies here– “bog bodies,” they’re called. I envision the peat extending deep below us, wondering how far down it goes and what creatures lay suspended in its spongy murk.

The lack of decomposition that leads to these preserved corpses also means that the bog stores carbon that would otherwise be released back into the soil or atmosphere. Peatlands are one of earth’s most efficient carbon sinks, covering a miniscule portion of earth’s landmass —about 3%— yet storing twice as much carbon as all of earth’s forests (NYT 2022).

Read that again: peatlands cover only three percent of earth’s land, but store twice as much carbon as all of its forests combined.

And yet, these ecosystems are imperiled. Peat has been harvested for fuel, peatlands drained for agriculture and architecture. Consequently, immense amounts of stored carbon are released back into the atmosphere as CO2, warming the earth. And as climate change worsens, more peatlands dry out, releasing yet more carbon: another self-fulfilling cycle.

To say nothing of the beauty of these places, it’s easy to understand why their existence is essential. It’s shameful that we’ve taken part in destroying them. We are only beginning to pay the penalty for it.

Mae & Kim

After reading the interpretive sign, my friends and I eat our snacks, each of us in contemplation of our 30-something year old bodies surrounded by this 7,000 year old bog. I think about the cycles of life and death that have sustained this place, the animals that walk upon the moss and later rest beneath it.

Eventually the eerie, single-note song of a white throated sparrow echoes across the open peatland. The bog’s reverie now broken, we chat and laugh and after a little while I wander off to start cataloguing the plants.

It’s astounding how many species grow here, each with its own unique adaptations to survive. Compared to the surrounding landscape, the bog isn’t what you’d call biodiverse, but given the conditions I am nonetheless surprised at the array of plant life.

Purple pitcher plants

Perhaps the most fascinating of the bog species are the pitcher plants, who get their nutrients not from the substrate or water, but from the bodies of insects that fall into their hollow tubes.

Purple pitcher plant, or Sarracenia purpurea, is the only pitcher plant native to New England. These alien-like plants collect water in their hollow leaves, in which insects drown. The insects, attracted to the fleshy red/green/purple pitchers, land on them and are then guided downward (and prevented from climbing back up) by directional hairs at the mouth of the tube-like leaf.

Young leaves secrete a digestive enzyme that aids in the breakdown of the drowned insects into nutrients the plants can absorb. Older leaves, however, also rely on the invertebrate and bacterial community that develops in the collected water to help break down their food. In turn the plant oxygenates the water held within their modified leaves, so these organisms can survive. Little oases of livable water within the bog’s acid nutrient desert.

Me holding one of the many newts we spotted in the forest on our way to the bog

While researching this post, I was startled to find that in addition to insects and other invertebrate prey, Sarracenia purpurea has also been discovered to capture young salamanders! Though, the plant’s ability to digest these much larger prisoners is unclear. Read more about it here.

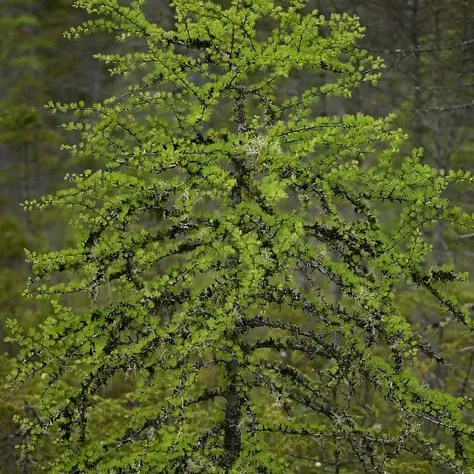

Tamarack, tamarack close up with mosses and lichens, and a barren black spruce trunk

Left: tamarack, right: black spruce

A lone black spruce, tall with a lollipop top. Thanks to Mae for this photo.

I’m surprised any tree can sufficiently anchor itself in the springy bed of moss, but black spruce and tamarack both find a way. The lack of nutrients stunts their growth, though the black spruce in particular seems to dwarf its surroundings, growing tall but rather barren aside from their “lollipop” tops. They emerge from the shrubbery like street lamps in a parking lot, scattered and solitary. Their leafless trunks are perhaps due to nutrient deficiency, but also may serve the purpose of helping them avoid blowing over during high winds.

From left to right, top to bottom: swamp laurel, leatherleaf, northern wild raisin, swamp laurel, sheep laurel, bog labrador tea

Most of the shrubs in both the Black Spruce Bog and the Dwarf Shrub Bog are in the heath family, which are largely evergreen: producing leaves once takes far less energy than doing so annually. Plants in this family are adapted to acidic conditions and are among the few species that grow well here. Leatherleaf, sheep laurel, and bog labrador tea are just a few of the ones I found.

Left to right, top to bottom: a bulrush, three-leaved falso solomon’s seal, fringed sedge, tall bog sedge, star sedge, and either two- or three-seeded sedge

Closer to the sphagnum I spot the petite, delicate white flowers of three-leaved false Solomon’s seal, several sedge species, and the tiny round leaves of the vine-like creeping snowberry. I look for sundew, another carnivorous plant common in Vermont’s bogs, but don’t spot any. Thankfully I’d be visiting two more bogs in the coming weeks and would find some there.

I wonder what makes this pitcher plant flower yellow?

Close up of the bright yellow pitcher plant flower

Kim & Mae enjoying the bog

I wander and photograph and wander some more, apart from my friends now but happy to hear them laughing a little ways off. I see butterflies and dragonflies and one pitcher plant flower that is bright yellow rather than the usual red. I am humbled by this place. I feel alive in a way that is both invigorating and nostalgic; perhaps the bog’s ancient spirit has touched my own.

My friends call me over to watch a tiger swallowtail meander lazily through the sun-soaked bog. I feel calm as I watch the elegant creature drift and flutter, swoop and cruise. She is in no hurry.

Luckily, neither are we.

If you are considering a visit to Peacham Bog, I highly recommend stopping into the Groton Nature Center. Not only is this where the trail begins, but the wonderful interpreter there was able to give me detailed information about the bog, plant life, and trail conditions (shoutout to Brian!). The center also features an array of beautiful exhibits ranging from glacial history to bog species. Well worth a visit.

All photos are my own unless otherwise noted. © Lorna Dielentheis 2025

This post was originally published here.