By Leslie Spencer, VMN Lower Winooski participant 2024

Bedrock, a noun and an adjective

Today, let’s talk about bedrock — both as a noun and an adjective. Bedrock, the noun, is the solid, ancient rock under our feet, and bedrock, the adjective, speaks to our core values.

As I shared in my welcome post, Mary Oliver’s words, “attention is the beginning of devotion,” are constantly bouncing around my brain. This fall, through the Vermont Master Naturalist program, I’ve been captivated by the story of Vermont’s bedrock geology. Understanding how the land beneath our feet formed is intriguing on its own, but sharing the experience with community of naturalists who share the same core values of protecting our planet and advocating for a better world makes it even more meaningful. Learning about the layers of the earth beneath us can provide many grounding lessons.

Reflecting on bedrock feels particularly poignant today, on the heels of a week where it feels like the bedrock of American politics has been shattered. Looking toward another four years of Trump’s authoritarianism is destabilizing, and I want to share a bit about how learning about natural history helps me stay grounded. Learning about the ancient natural history of our place can teach us lessons of resilience and endurance today.

A handful of bedrock – Iberville Shale and Dunham Dolomite – at the Champlain Thrust Fault; a gathering of Vermont Master Naturalists at the Thrust Fault.

Vermont was once at the bottom of an ancient tropical ocean

Long story short: About 500 million year ago, Vermont was at the bottom of the Iapetus Ocean, a tropical sea that once stretched across the Equator. Through a dynamic geological history of tectonic plate movement, continental collisions, volcanic action, and years of erosion, present-day Vermont is made up of a stunningly diverse array of bedrock types. Mountain building events (the Taconic Orogeny and the Acadian Orogeny) essentially bulldozed paleocontinents together, folding and uplifting the floor of the ancient Iapetus Ocean into what we know as the Green Mountains today.

Dunham dolomite, for example, is one of the bedrock types that lies beneath our feet in Burlington, Vermont. It contains calcium carbonate from ancient sea creatures that lived in the Iapetus Ocean. I mean, how cool is that??!

Note: If you’re interested in a longer version of the geology story, it’s at the bottom!

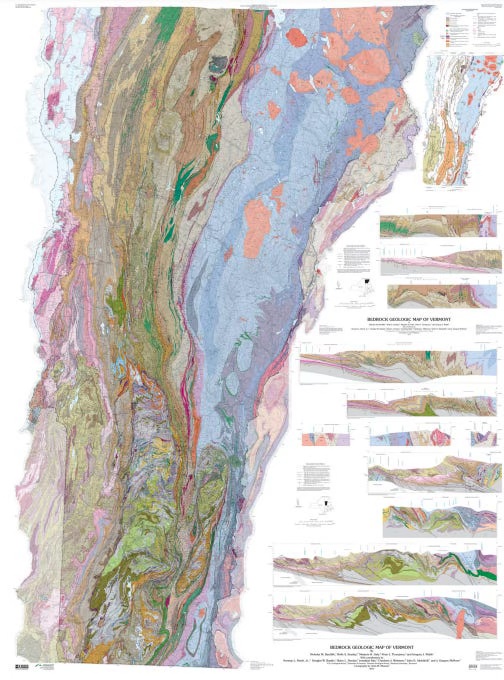

Vermont’s bedrock is a beautiful mosaic of rock types, because of a dynamic geologic past, full of millions of years of tectonic drama and mountain building events. Access a high-res version of the map here.

A cephalopod fossil on a rock face in Northwestern Vermont. Learn more here.

Red columbine (Aquilegia canadensis), my favorite spring wildflower, is found in well-drained, calcium-rich soils like the bluffs at Rock Point in Burlington, Vermont. Here, the bedrock is Dunham Dolomite, which formed from bottom sediments, including ancient sea creatures, in the tropical Iapetus Ocean, about 500 million years ago.

Why does all of this matter?

All of this tectonic plate drama has left us with a fascinating landscape in Vermont, with a mosaic of bedrock types with real, everyday implications:

- Natural communities: Over time, bedrock weathers to form soil which support life. For example, we find lots of spring ephemeral wildflowers in areas rich in calcium from bedrock that dates back to being the bottom sediments of the Iapetus Ocean millions of years ago.

- Agriculture: The bedrock beneath our feet influences the fertility, permeability, and pH of agricultural soils, impacting what kind of food can be produced in the region.

- Hazards: Some areas are more vulnerable to hazards than others – like earthquakes and landslides – depending on the bedrock at our feet.

- Human infrastructure: Bedrock provides building materials. For example, the Monkton quartzite at Burlington’s Redstone Quarry was originally sediment on the floor of the ancient Iapetus Ocean, too. Today, it’s used in local construction.

By studying Vermont’s complex bedrock geology, we gain a richer perspective on how the land has formed over time and how it continues to shape the natural landscape and the fabric of our community today.

Hepaticas, spring wildflowers that thrive in calcium-rich soils (Leslie Spencer); blueberries, a food crop native to the Northeast (Leslie Spencer); a landslide off of Riverside Ave in Burlington, VT (Glenn Russell/VT Digger); Burlington’s Redstone Quarry (Sean Beckett)

Lessons from bedrock in a changing world

So, what can Vermont’s bedrock geology teach us in a time when the values that ground us as a community, and a nation, feel so shaken?

- Diversity & interdependence: Just as Vermont is made up of an amazing variety of bedrock, our communities rely on a diversity of ideas, values, and voices. Each type has a role in creating a resilient whole, and we need them all.

- Slow and steady change: Tectonic plates move at the speed our fingernails grow – not fast, but also not imperceptibly slow. To sustain ourselves for the work ahead, we need to think of it as a marathon, not a sprint.

- Finding our bedrock: In uncertain times, we will find strength in our communities, our landscapes, and the grounding practices that help us stay sane. Just as bedrock provides the foundation for natural communities to thrive, our “bedrock” people, places, and values will help us push forward into four scary years ahead.

In sum, attention – to the patterns and processes in the natural world – is the beginning of devotion – to a more sustainable, compassionate future, where people and places are treated with respect and compassion, rather than distrust and fear.

Resources

A mélange of resources that came together to inspire this post, if you feel like diving in some more:

- Feeling the cracks in the bedrock of American politics to your core? Check out 10 ways to be prepared and grounded now that Trump has won. Thanks Grace Oedel& Christine Tyler Hill for circulating this article on your platforms.

- Sean Beckett, of North Branch Nature Center, speaking on the bedrock geology of Montpelier, Vermont here.

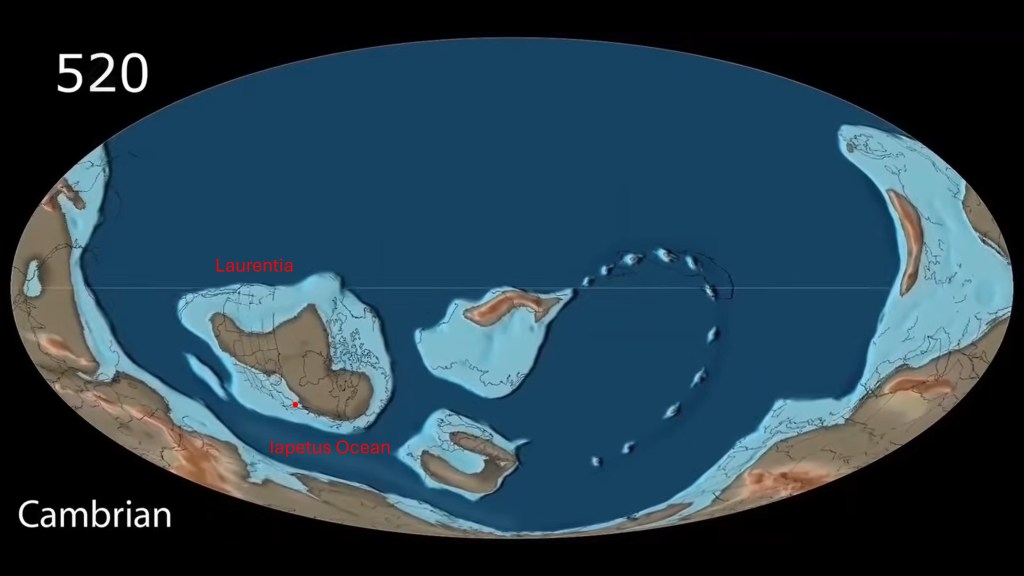

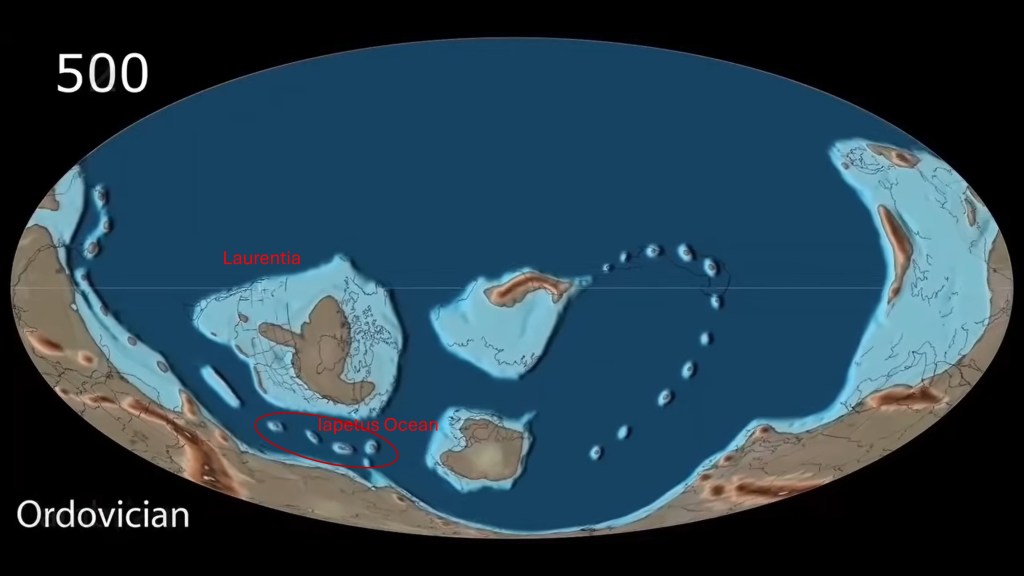

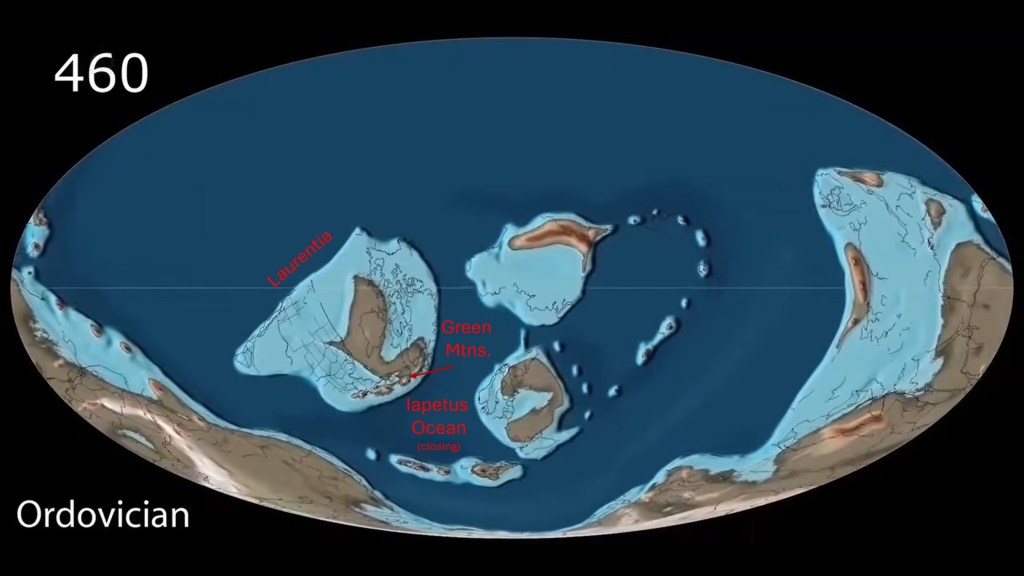

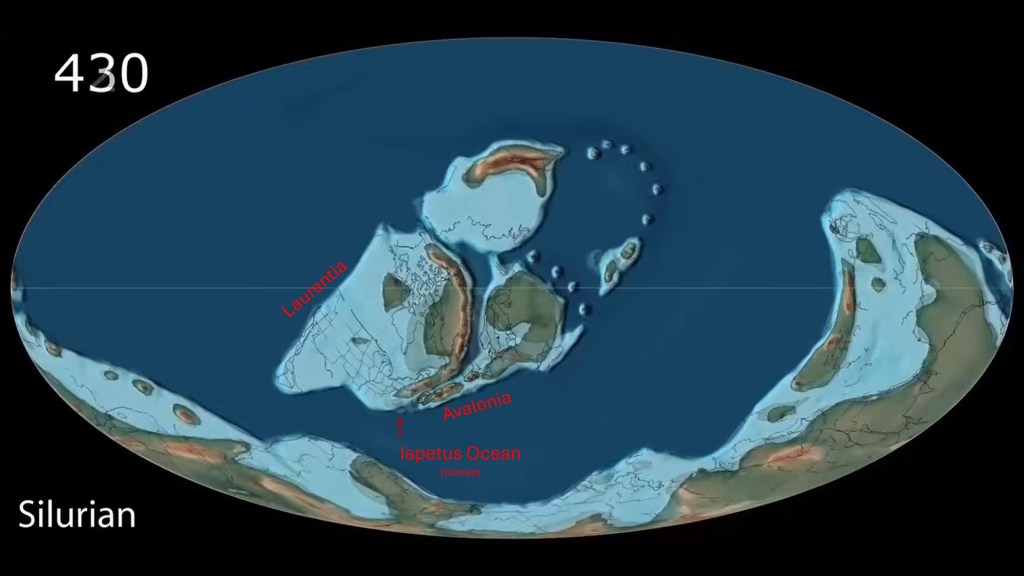

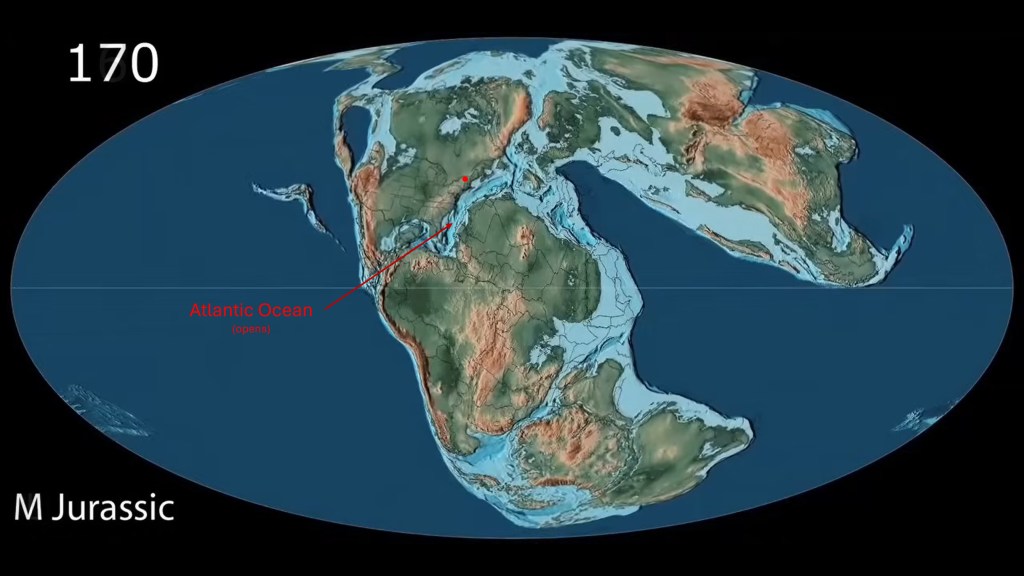

- The annotated plate tectonics photos below come from this animation.

- Lots of detailed bedrock geology maps here.

- There’s a reef? In Vermont? Learn more here.

Vermont was once the bottom of an ancient tropical ocean: The Longer Story

A tropical ocean and Laurentia: Our bedrock geology story today begins about 500 million years ago, during a time before land plants and animals existed, though they were soon to come (the Cambrian Explosion). Humans were still far in the future (early humans appeared only about 2 million years ago). At this time, most continents were in the southern hemisphere, surrounded by warm, shallow seas. The paleocontinent Laurentia, the precursor to North America, lay sideways along the equator. The red dot on the map below marks where Vermont would have been – completely underwater in the Iapetus Ocean.

Formation of the Green Mountains (the Taconic Orogeny): Next, we see a chain of volcanic islands beginning to emerge along Laurentia’s edge (circled in red). Think of them as similar to present-day Japan. As tectonic plates converged, the Iapetus Ocean started to close, and these islands slammed into Laurentia, forming the Green Mountains. The Greens now created Laurentia’s eastern edge, and began eroding into the Iapetus Ocean, with sediments from the mountains settling on the ocean floor.

Formation of Eastern Vermont, New Hampshire, and Maine (the Acadian Orogeny): Then, in comes the paleocontinent Avalonia, bringing in present-day Eastern Vermont, New Hampshire, and Maine. Colliding in a “multi-car pileup”, the sediments from the ocean floor were brought up into the mountains. Vermont then became landlocked, no longer near an active tectonic plate boundary.

The formation and breakup of Pangea: Over the next few hundred million years, tectonic plates continued to move, but with little effect on Vermont, since it became landlocked. Pangea, the supercontinent, formed about 2-300 million years ago, and then about 150 million years ago, Pangea began to break apart into the continents we know today, forming the Atlantic Ocean as a result.

The end.

You read so far you deserve a ✨fun fact✨: The Atlantic Ocean gets its name from Greek mythology. The titan Iapetus was the father of Atlas. Just as Iapetus preceded Atlas, the Iapetus Ocean was the “parent” ocean to the Atlantic.