By Kate Taylor

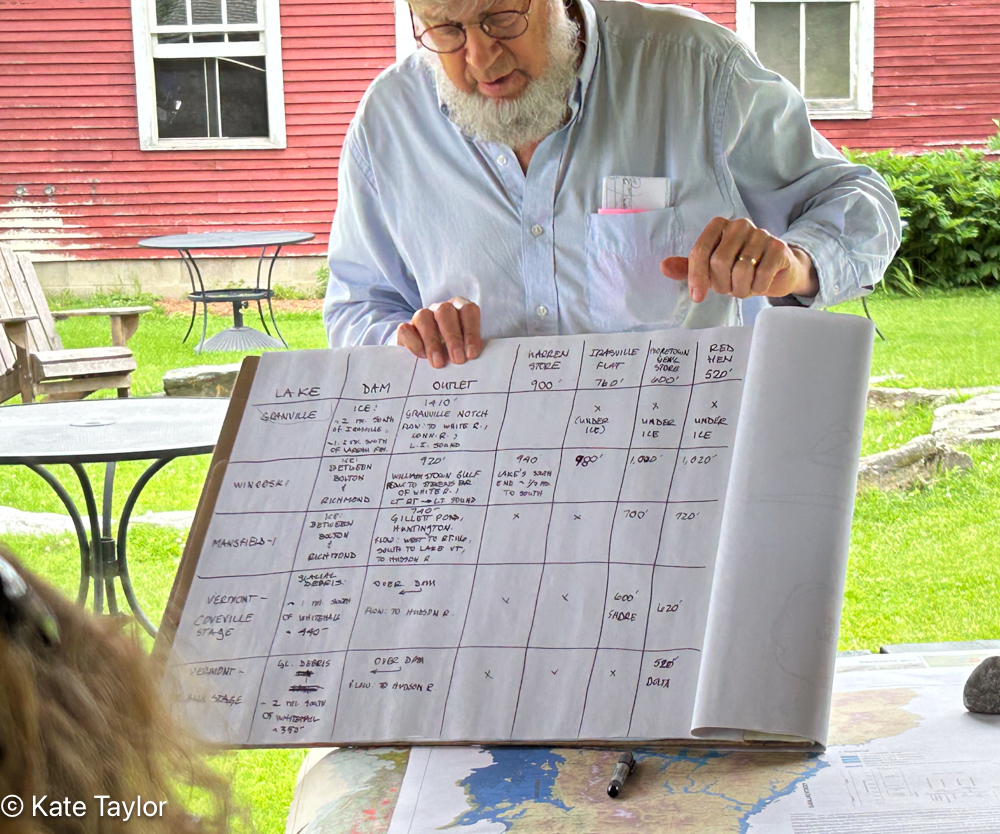

Recently I spent the day as part of the Vermont Master Naturalist Program learning about world history. I don’t mean wars and kings. I mean the movement of continents and glaciers. I mean history where time is measured in eons and eras. We were taught by Craig Heindel, a Vermont hydrogeologist as well as a fascinating and enthusiastic instructor.

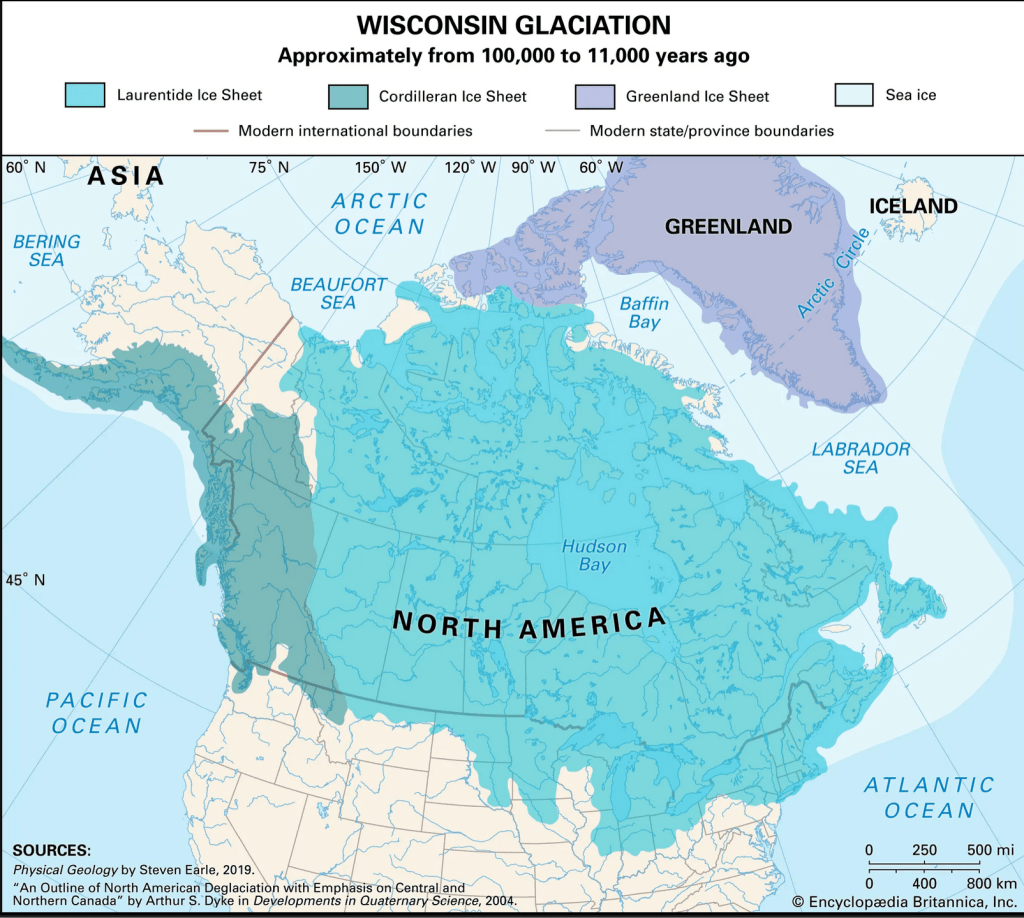

He told us how a few million years ago the world was in an ice age. There were periods of freezing and thawing, some lasting hundreds, or even thousands of years, but the overall trend was ice. Around 25,000 years ago a giant glacier called the Laurentian Ice Sheet, reached its maximum size, covering most of Canada and dipping into the United States. All of New England was buried under more than a mile of ice. Mount Mansfield was buried under ice.

Camel’s Hump was covered in ice. Mount Washington was likely topped with ice. There was so much water trapped in the glacier that it lowered the ocean level by around 600 feet (six hundred feet!). You could have walked over ice to George’s Bank. It would have been an unrecognizable landscape.

Wisconsin glaciation, Encyclopædia Britannica https://www.britannica.com/place/Laurentide-Ice-Sheet#/media/1/332438/258684

Access Date July 1, 2025

Interesting, you may be thinking, but that was a long time ago, it has nothing to do with me and my modern interests. Oh, but it does matter. That is the amazing thing.

Let’s talk about rocks for a moment. Bear with me, it’s related. What is a rock? Basically, it’s a chunk of minerals. Occasionally a rock is comprised of a single mineral, more often they are a combination of many different ones. Nitrogen, phosphorus, magnesium, silver, iron, and calcium carbonate are some of the many, many, minerals that make up rocks.

Rocks are defined by the minerals they contain and the molecular structure of those minerals. The structure determines the hardness of the rock. Some rocks are soft, while other easily chip or flake. Some seem indestructible. Rocks can be boulders, sand grains and everything in-between. Rocks are easy to take for granted.

Map of various lakes that were formed in the Mad River Valley over the past ten to 25 thousand years. The different colors show the extent of different lakes. (Map created by Craig Heindel, using the VT Agency of Natural Resources’s Natural Resources Atlas)

Now, back to all that ice. Imagine it melting. That’s a lot of water. As it melted the water had to go somewhere, but the glacier itself blocked the water from flowing North into the St Lawrence as it does today. Instead, the water flooded Vermont creating gigantic glacial lakes between and among the Green Mountains. Periodically a portion of the gigantic ice dam that was the glacier would give way with a catastrophic torrent of water that gouged the land and scoured a path as it rushed downhill. Other times, the melt was a slow trickle, wearing away the land.

This brings us back to our rocks. Flowing water not only carves out the landscape, it also carries rocks, soils and sediments along with it. A fast-flowing river can tumble rocks breaking them down into sand and the smaller sediments that make up clay, releasing the minerals into the water. Some minerals are dissolved, remaining in the water until the water evaporates, some simply break into smaller particles that can be taken up in other forms.

(A bobcat for instance, crouching to drink at the river’s edge will lap up the minerals in the water it drinks, or your well dug 200’ into a subterranean lake contains minerals leached into it from the surrounding soil. Plants too, drink in those minerals with roots stretching down into the soil.)

When the river reaches a wide, shallow area, it can create a lake or pond. As the water slows it dumps the heavier particles first, while the lighter ones drift further out until they eventually settle. That means that near shore the soil is sandy and contains heavier particles while further out the sediment becomes finer. When the river changes course or the lake disappears the soil remains behind, stones, sand, clay or some mix.

If you travel to those spots today you can find evidence of those lakes in the landscape and in the soil. Places that were in the center of a deep lake tend to have clay, while spots where a rushing river ended are more likely to be sand.

In other words, the ground beneath our feet was influenced by the movement of all that ice and water. Not only the shape of the land, but the quality of the soil itself. All life has its preferred habitat and in Vermont that habitat was influenced by the glacier that covered it for thousands of years. The life in Lake Champlain, the clay for bricks and pottery, rich or poor fields for farming, the water in your well and the soil in your garden can all be traced back to a time before humanity covered the earth.

It’s a reminder of how we are not separate from this great planet we live on, but rather fit into our own specialized niche as does all life on earth.

*Disclaimer: My knowledge is shallow and my explanation is an oversimplification. Craig is a great instructor, and any mistakes are mine alone.

Thanks for looking,

Stay well, be curious, love diversity,

Kate

July, 2025

This post was originally published here.