By Rachel Mullis, VMN Lower Winooski participant 2024

Under a canopy of red oaks on a balmy day in September, a couple dozen nature lovers descended on Burlington’s Killarney Avenue. As newly minted members of the Vermont Master Naturalist’s 2024/5 Lower Winooski River cohort, this was our first day getting up close and personal with Vermont’s natural history. Amid the thunk of acorns that fell steadily in the breeze, each person introduced themself and shared their favorite aspect of natural history. Some expressed their love for plants, others for animals or the interactions between the two. Few people had much to say about geology.

Geology is the science and history of the earth’s physical structure and substance and the processes that act on it. VMN Director and Founder Alicia Daniel lamented that this oldest component of natural history — also referred to as the base of the layer cake — tends to get short shrift. It’s true that studying rocks may not seem as engaging as finding a rare plant or a set of bobcat tracks. But as Alicia and our VMN cohort leader, Laura Meyer, would show us, geology can be quite dramatic. And it sets the stage for everything that comes next.

Exploring Rock Point’s many natural mysteries

After introductions, the group headed south on the Burlington Greenway toward Rock Point. Our first geology clue for the day was the buff-colored Dunham Dolostone quarried onsite to build the steps that led us up to Rock Point’s Holy Trinity Trail. From there, we took a moment to close our eyes and sharpen our other senses.

“Quietly observing with all senses is a gift that not all get to experience,” wrote Mary Landon in her notes about the day. “I am grateful I can be in these environments readily.”

We also heard from VMN Alumni Jacob Holzberg-Pill, who provided some engaging history about the trees and plants in our path and how early settlers shaped their prevalence. “He shared his passion for trees and living lightly on the Earth, with plenty of humor thrown in,” Mary wrote.

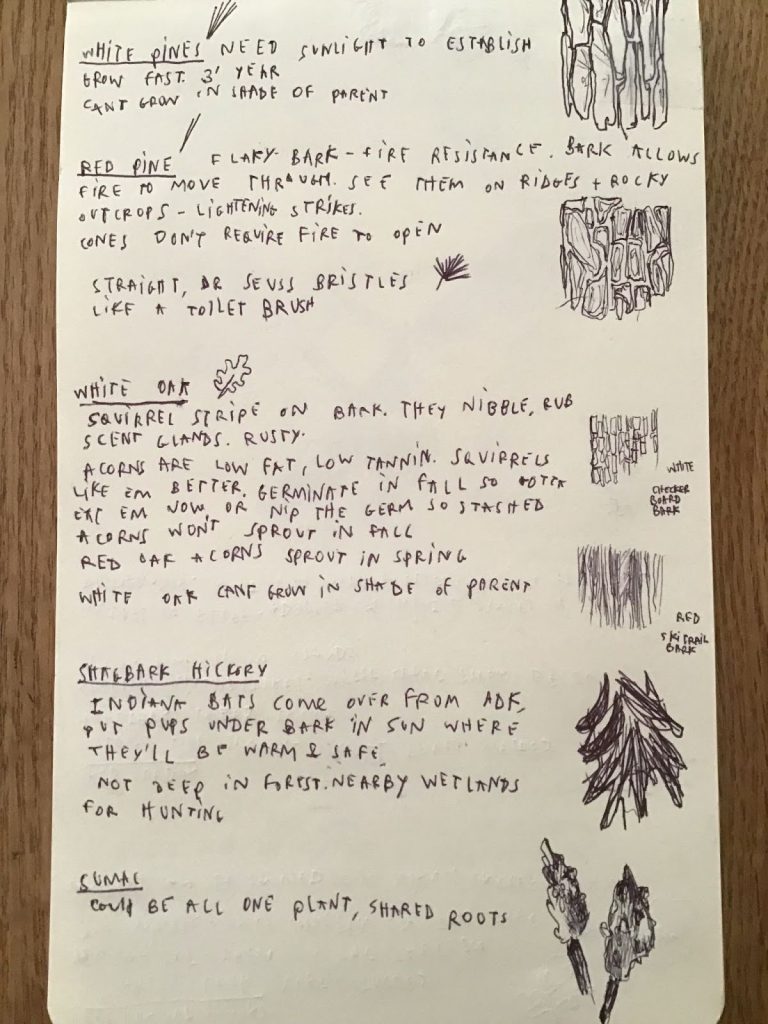

Micah Barritt captured Jacob’s anecdotes and observations from Laura and Alicia in relation to sketches of each tree species we discussed. For example, white pines can’t grow in the shade of their parents.

Red pine’s flaky bark is fire resistant. Shagbark hickory’s flaky bark acts as a nursery for Indiana bat pups. And a stand of sumac, which reproduces clonally, may consist of just one plant

We meandered down the Trail Access Road to an open field and three “steps to nowhere” that marked where a school once stood. We stopped often to consider mysteries large and small. One: bloated woody growths that turned out to be Bitternut hickory galls. Another: nut shells on tree stumps that marked where squirrels had dined and slugs moved in to clean up the mess.

“The ‘places,’ some hidden, all around us tell their stories: stone walls, foundations, old roads and fields, rock outcroppings, tree species, planted grids of trees, and bodies of water (or lack thereof),” Mary wrote.

We observed pasture trees in stands of young forest, marked by their wide, leafless branches. We passed a vast field of wildflowers brimming with goldenrods and asters in riotous blues and purples that benefited from this year’s plentiful rain.

Studying the world-famous Champlain Thrust Fault

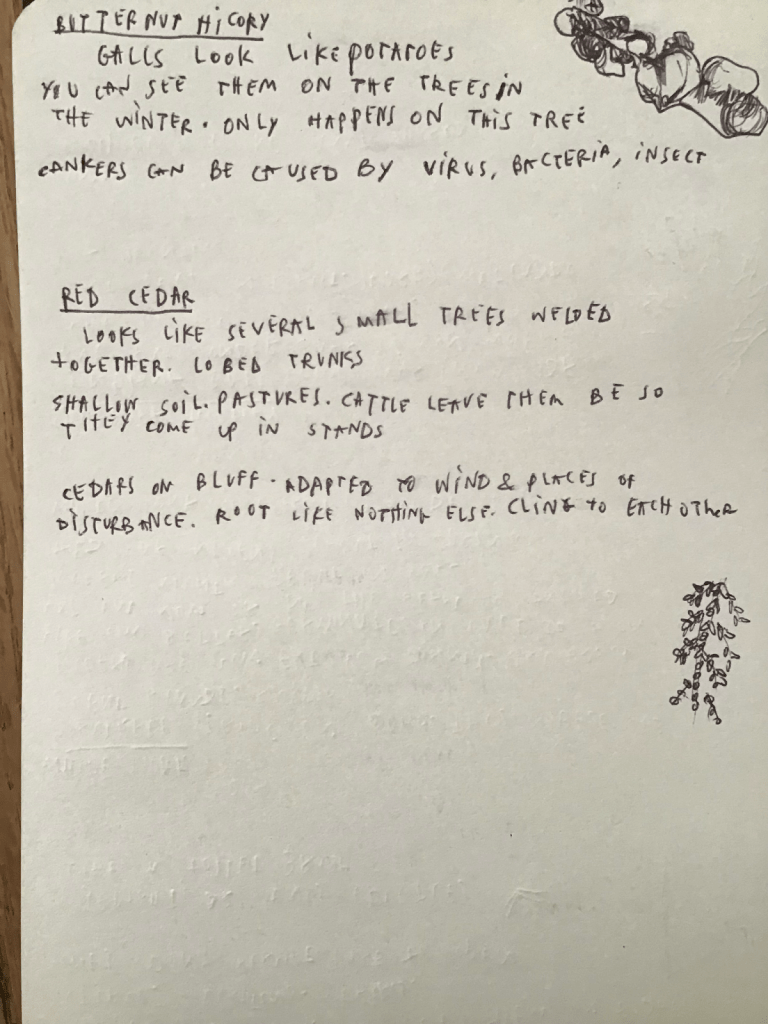

Our group eventually descended into the forest again, heading west toward Lake Champlain. We clambered down steep steps among the roots of ancient cedars until we reached the main event: the Champlain Thrust Fault.

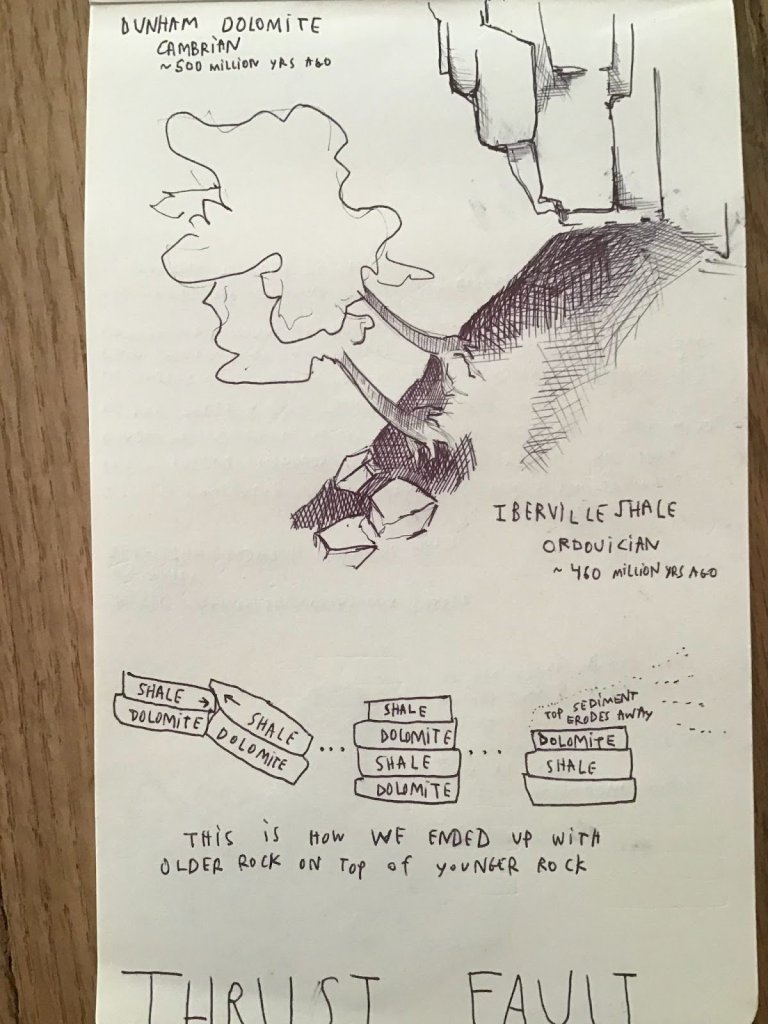

Our prework for the day was to watch a video titled Montpelier Underfoot, which covered the formation of Vermont’s bedrock dating back 540 million years ago to the Cambrian Period. Alicia and Laura supplemented this information with geology handouts we read as we ate lunch, looking up at two layers of history so old they were nearly impossible to comprehend. The Dunham Dolomite, formed around 500 million years ago, and the Iberville Shale, roughly 50 million years younger, were stacked like alphabet blocks, the older layer resting on top, askew and jutting out over open air.

“I hadn’t realized [the thrust fault] was so easy to access and so visible,” wrote Julia Lynam. “I found it breathtaking and almost hard to focus on as it reflected the afternoon sunlight shimmering off the lake. The contrast between the two rock layers was extreme and impressive.”

“Our planet is dynamic and always changing,” Mary reflected. “In our lifetimes we are not likely to see big changes, but we know that land masses are generally moving west at the rate of fingernail growth.”

Julia broke down some of the group’s main findings as follows: “The thrust was formed during the Taconic Orogeny, around 440 million years ago, from layers of Cambrian dolomite and Ordovician shale. When the layers split vertically under tectonic pressure, the eastern section was forced over the western section; then the top layer of Iberville Shale was eroded over many years, and we ended up with a layer of 542-488 million-year-old yellow Dunham Dolomite on top of a layer of 488-443 million-year-old black Iberville Shale, i.e. the older rock on top instead of underneath. Wow!”

“Also impressive, I think, is the effort and research on the part of many people that has over the centuries gone into understanding, at least as far as we can, the evolution of the Earth’s surface and the many processes that have led to the topography we see today. We’re privileged to live at a time when so much is known and understood, although, of course, there’s always more!”

Micah provided a visual rendering of the thrust fault. Mary marveled that “we live in a geologically rich area. In particular, the creation of the Champlain Valley and the Green Mountains show how our state is divided into two major areas: what is west of Montpelier and what is east of Montpelier. For a small state, we have a great diversity in bedrock types. Natural features such as the thrust fault at Rock Point and Chazy Reef in Isle La Motte are well-known examples that illustrate some of the State’s early geological development.”

A new appreciation for the ground underfoot

After plenty of discussion with Alicia and Laura, it was time to climb the Sunset Ridge Trail and explore the thrust fault from above. We pulled out our Wetland, Woodland, Wildland: A Guide to the Natural Communities of Vermont book to assess the rather peculiar natural community we found ourselves in. Alicia tested the soil’s pH to confirm the highly alkaline soil and calcareous substrate that nurtured this Limestone bluff cedar-pine forest.

From there, we continued on until we reached the Outdoor Chapel, reflecting on what we’d learned and sharing gratitude. I said I was grateful for our different ways of knowing and my newfound appreciation for the mysteries of the natural world. Maybe knowing it all wasn’t the point. Alicia said it reminded her of the idea that our possible knowledge grows as we learn, like a balloon that expands its boundaries as we fill it with more air.

Mary wrote this: “Our walk into Rock Point park and trails was all about reverence. What I love is that Alicia and Laura exude an attitude of complete appreciation and awe for the natural world. It was a day for observing details and sharing our enthusiasm for nature’s formations. Jacob Holzberg-Pill joined us for part of our day, sharing his passion for trees and living lightly on the Earth, with plenty of humor thrown in.”

“Our first field trip as a group was full of new faces and friendships, collaborations, and ideas for how to share our new-found knowledge with others,” she continued. “Such a wonderful thing to close our eyes as a group, listening to the breeze in the pine needles and the jarring sound of falling acorns.”

As we passed another bluff, I noticed a Downy goldenrod growing contentedly in the exposed glacial till: a great teaser for our next field day about glacial geology! Someone asked Laura how she records the knowledge she gains after a full day in the field. She said the first thing she does when she gets home is rewrite her notes while everything is still fresh in her mind.

I decided to take her advice, and found myself drawing a map of our route. Alicia shared that this is a technique called an event map, popularized by Hannah Hinchman’s book, A Trail Through Leaves: The Journal as a Path to Place. I appreciated how drawing opened me up to new ways of remembering my experience. Hopefully documenting our collective notes and observations over the course of this year will help us all remember things in greater detail.

Rachel Mullis